Prince Shell

in memoriam (b. 12.31.28 Lott TX - d. 4.11.07 Scottsdale AZ)

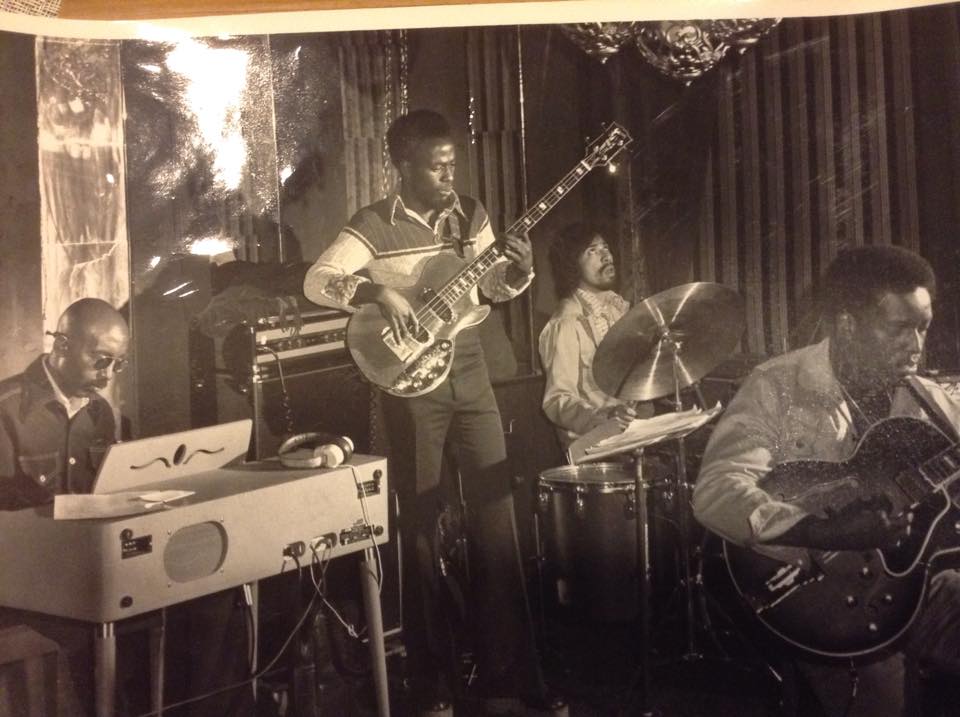

Prince Shell (Wurlitzer electric piano) with the Jerry Byrd Quartet at the Century Skyroom, 1140 East Washington Street, Phoenix AZ. Jerry Byrd-guitar, Ronnie Scott-electric bass, John Flores or George Carrillo, Jr. (?) - drums, 1975. I heard this band during this gig, probably my fourth time hearing Prince play live. The club was open from 1961-1982 and Prince was a regular there. Photographer unknown.

See Ted Goddard’s website for more on Prince Shell:

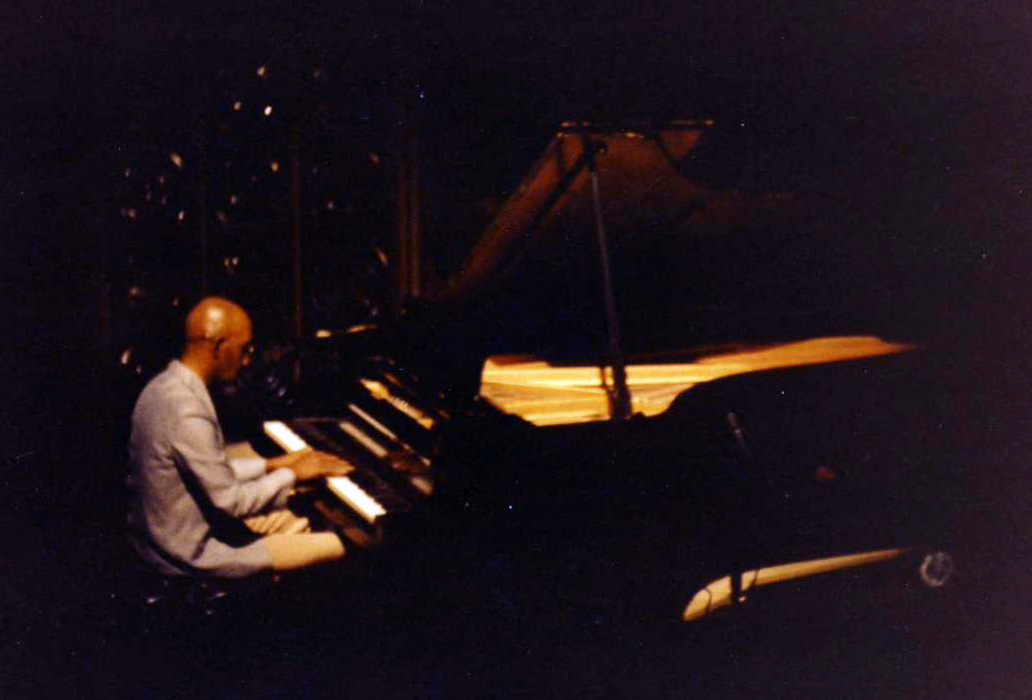

Prince Shell at the piano, 2001. Courtesy of Ted Goddard.

About Prince Shell

Prince Shell was a great musician: a highly skilled, imaginative, original arranger and pianist who worked from the late 1940s to the early 2000s. He was also a kind and generous mentor and friend; a very humble, patient, and spiritual person; a great lover of all kinds of music; and an informal teacher and mentor who gave time and support to many young musicians.

Here are some notes (slightly edited and updated) that I wrote to the jazz-research listserv (an online group of several hundred jazz researchers) after Prince’s passing in April 2007:

I'd like to record the passing of my friend and mentor, pianist/arranger/former valve trombonist Eutrice Ulysses "Prince" Shell (b. 31 Dec 1928 Lott TX, d. 11 Apr 2007 Scottsdale AZ). I don't believe he's listed in any history books, but he was a significant musician and teacher, especially in Chicago and Phoenix.

Some facts about his life in jazz:

• He moved from Texas to Chicago around 1943 and completed high school at DuSable High School (senior year) playing in ensembles under Captain Walter Dyett. (See below* for more about Captain Walter Dyett and DuSable High School’s music program and alumni.) He studied valve trombone, trumpet, and alto saxophone. He was mostly self-taught on piano, although that later became his main instrument.

Prince remained friends with Pat Patrick, Malachi Favors, Bruz Freeman, Pete Cosey, and many other Chicago musicians, many of whom visited him in Arizona from the 1970s up to his last few months. Muhal Richard Abrams was among the many Chicago musicians who told me they remembered him as an excellent arranger. George Lewis wrote me in 1997 “…I used to observe [Prince Shell] from afar as kind of a legendary Chicago arranger. I may have even played some of those arrangements; I think Pete Cosey introduced me.” And, on Prince’s passing in 2007, Roscoe Mitchell wrote me that “He will be missed by so many.”

•He attended Tennessee State University in Nashville, where trombonist Jimmy Cleveland was a fellow student. Prince was an arranger and mallet player in the Tennessee State Collegians. See the article “Jazz in Historically Black Colleges,” Andrew L. Goodrich Jazz Education Journal November 2001.

He attended the Navy School of Music as well.

• He was one of the people who recorded an amazing set by Charlie Parker at the Pershing Hotel in Chicago on October 23, 1950; his recording was from the front of the stage, better than the often issued, poor quality dressing room speaker recording. Shell's two tape copies were lost, one stolen and the other given to a British record label and never returned (or issued?).

• He played valve trombone with Gene Ammons’ group, and piano with Wardell Gray, Claude McLin, and many others. He recalled getting in trouble for laughing on a gig with McLin when Wardell Gray was sitting in (and cutting McLin).

• He told me he was with Gene Ammons during one of Ammons' arrests; this traumatic experience with police helped motivate Shell to join the military and get away from the Chicago scene of the time.

• He was the uncredited arranger of the version of "Possession" (composed by Harry Revel) on Sun Ra's Sun Song, originally issued as Jazz by Sun Ra (Transition, 1956). Sun Ra added one horn to Shell's arrangement (which I have). He also wrote two unrecorded arrangements for Sun Ra, "Memoirs of a Jug" and "Lady Bird." In 1990, John Gilmore told me Prince Shell's charts were "still in the book."

• He was pianist and staff arranger for an Air Force big band at Offutt Air Force Base (home of Strategic Air Command) 1955-59; Boston jazz DJ Tony Cennamo played trumpet in the band. He also served in the Navy for a year and a half as a musician, attending the Navy School of Music in Washington, DC in the late 1940s.

• Prince wrote a "symphonic fantasia" (his description) on Sonny Rollins themes, probably in the 1950s, apparently lost, and showed it to Rollins at the time, but it was never fully performed. Rollins remembered him and visited him in the Scottsdale nursing home after a gig in November 2006 (see photo below).

• He toured the world in the early 1960s as Gene McDaniels' pianist and musical director. I don't know whether he appears on any of McDaniels' recordings.

• He was house pianist at the Regal Theater in Chicago in the mid-1960s, sometimes accompanying or writing arrangements for Motown and other R&B stars.

• He told me he was invited to join the AACM in its early days, but couldn't reconcile their policy against playing standards with his need for an income as a working musician.

• During most of his lifetime, his only credited LP appearance (as far as I know) was on a Jesse Jackson record (On the Case: The SCLC Operation Breadbasket Orchestra and Choir, Chess LPS 1549, 1970) playing chimes and listed as arranger of four songs on the album. Donny Hathaway, Phil Upchurch, and Paul Serrano are among the 27 musicians listed on the album.

• He wrote commissioned charts for the short-lived Sam Jones-Tom Harrell big band. In the 1970s and '80s, his house was filled with piles of his hundreds of arrangements, mixtures of record copies and strikingly original writing. (I never saw his name on one of his charts, no matter how original they were -- claiming authorship seemed to go against his philosophy and extremely humble and self-effacing personality.)

• A 2002 CD reissue of R&B duo Eddie & Ernie's Lost Friends (Kent CDKEND 214) credits his arrangements on some tracks.

• He returned to Phoenix, AZ by 1971 and was a mentor to me, Lewis Nash, Ted Goddard (Jr.), Jim Henry, Tom Goodwin, and many other jazz musicians growing up or living in Phoenix, introducing us to rare records, bebop history, all kinds of tunes, and obscure and forgotten players of all eras. He was an avid record collector and listener, and made many cassette tape compilations for friends and young musicians.

• Based in Phoenix most of the time from 1971-2007 (except when he returned to Lott TX for a couple of years in the early 1990s to help family members), he led big bands on and off, played local gigs (with guitarist Jerry Byrd, drummer Dave Cook’s band Vanguard, Lewis Nash's Pendulum, etc.), coached and accompanied singers, wrote for special concerts, including the Roots of Jazz series produced by Mary Bishop, and received occasional commissions. Ted Goddard (guitarist, son of the tenor saxophonist) has led a tentet devoted to Shell's music since 2001. The tentet is still meeting weekly at the musicians’ union hall and playing Prince Shell’s music as of 2024.

Prince Shell playing his solo piano set at a concert produced by Lewis Nash and Allan Chase, “An Evening of Creative Improvised Music,” ASU Music Theater, Tempe AZ, 1.21.80.

Allan Chase & Prince Shell, hanging out and listening to records, July 19, 2006 in Phoenix.

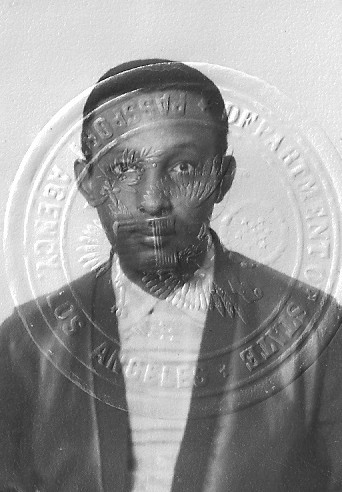

Prince Shell’s passport photo, 1962, around the time of his world tour as Gene McDaniels’ musical director and pianist.

December 1975 flyer for El Bandido. Prince Shell was the pianist in the Pete Magadini Quartet.

Articles about Prince Shell by:

Patricia Myers August 2006

Patricia Myers Jazz in AZ Newsletter, May-June 2006

Suzanne McElfresh ca. 1980, Phoenix New Times

Paul Cantrell on Pete Magadini (and Prince Shell) Phoenix New Times, date unknown

Letter from Dr. Warrick Carter

Bird & Bebop Program, Roots of Jazz Series, Part II, February 1980

More Photos of Prince Shell:

Tennessee State Collegians (Prince Shell on mallets in back left)

Dave Cook (11.5.33-8.30.13)-vibes & drums, Ray Yancy-bass, Jim “Zeke” Zoeckler-tenor sax, and Prince Shell, The Blue Notes, ca. mid-1960s (?) in Phoenix.

Click to open a PDF of the score of Prince Shell’s “My Funny Valentine” arrangement.

If you’re interested in parts, contact me. (This is a concert recording from the board — not an ideal balance.)

Personal Memories Of Prince Shell in Phoenix

Prince Shell was one of the handful of people (along with Charles Lewis, Frank Smith, and a few others) who made a life in jazz seem possible to me. Knowing a creative, serious musician like him was inspiring and fascinating. And realizing that someone who was not famous could still be a vital participant in the music, and one who was fully respected by his peers, including many well-known jazz musicians, was something that shaped my life and interest in music. He had a profound effect on the lives of many people in Phoenix (and, I later learned, in Chicago, Nashville, and at the military bases where he served) and raised the level of music in our city.

My father and his pianist-vocalist friend Karl Woodman heard Prince Shell in Phoenix in the 1960s, when I was a small child. Prince was in and out of town at various times, as his mother lived in Phoenix, in a house Prince later lived in for many years at 2702 E. Atlanta in South Phoenix.

I had grown up hearing great jazz, including Miles, Monk, Mingus, Art Blakey, the MJQ, etc. since birth, thanks to my parents, so I had something to prepare me for Prince Shell. I was fascinated by Prince’s playing and writing as soon as I heard it. It was apparent that he was a real artist with a unique voice, a full command of bebop language, and some “out” modern, original ideas. I first heard Prince Shell around 1973 with Dave Cook’s Vanguard at a supper club, Reubens on Camelback at 18th St. (adjoining Coco’s coffee shop), probably with Vic Kottner on bass, Frank Smith and maybe also John Hardy on saxes and flute, and Dave on drums and vibes, and opening for a jazz concert at the Celebrity Theater (Les McCann, maybe?). In spring 1975, my friend Brooke Michal took me to the Century Skyroom to hear Prince with the Jerry Byrd Quartet, and soon after that, I first heard his writing when I went to the Skyroom for some of the open mic talent nights that he would host, leading his MasterCharge big band in the first set. Tom Miles, who was about to leave town with an ice show, played a beautiful version of “I Remember Clifford” on flügelhorn. After the big band set, literally anyone could sit in, and I got a sense of Prince’s values and the respect he had in his community. I remember a man who said his name was “James Brown, the President of Soul” wanted to dance to “Skin Tight” by the Ohio Players, which the band had to learn from the jukebox. When the band had learned enough of it, they unplugged the jukebox in mid-song and went into the groove, and he danced wildly around the stage and soon was writhing on the floor. People were soon standing up, heckling him and throwing things. Prince Shell, very uncharacteristically (because he was a very quiet, patient, and humble man) stopped the band and stood on his piano stool, admonishing the audience: “This man is expressing his soul, and you are attacking him.” People respected Prince and quieted down. Later, an amateur singer asked to sing “Feel Like Making Love,” coincidentally written by Gene McDaniels, with whom Prince had toured the world as musical director 12 or so years earlier. She was lost and very nervous, modulating to a new key on every phrase, and Prince followed her harmonically with mind-blowing accuracy — and kindness.

On the other hand, when I was at the Skyroom hearing the Jerry Byrd Quartet playing an instrumental version of “Feel Like Making Love,” Prince closed the lid of his old tan Wurlitzer electric piano and bowed his head, taking a silent solo for one chorus, then looked up, nodded, and they played the tune out. I wrote out a “transcription” of this (“close lid,” 32 bars of rest) and gave it to my ASU jazz professor, Dan Haerle, who had it on his office wall for a while.

In 1975, we used to go to El Bandido, a Chinese-Mexican restaurant at 1617 E. Thomas, to hear Pete Magadini’s quartet. They played Thursday through Sunday — from 9 PM to 4 AM on Friday and Saturday nights, the only after-hours jazz I recall in Phoenix. The band was Jim “Zeke” Zoeckler-alto and tenor sax, Prince Shell-piano, Curtis Glenn-bass, and Pete Magadini-drums. Pete was a famous drum teacher with an advanced polyrhythm book that everyone attempted to use, but in this context he was also a very musical, swinging ensemble player and a hip bandleader. The group played serious bebop and standards, including a drum feature dedicated to Billy Higgins, “Smiling Billy,” and the real jazz fans came out to hear them. Prince sounded great in this group and got a chance to stretch out a lot. The one thing Prince would not do is play a solo in time at a very fast tempo, like an up-tempo rhythm changes tune. He would say he played “arranger’s piano” and he felt he couldn’t do what he heard in his head — what Bud Powell would play, for example. (In reality, he could play bebop very fluently and wasn’t really that limited technically, but he didn’t like playing at 300 BPM.) So he would sometimes play Debussy’s “Clair de lune” in slow, rubato motion, over the cooking rhythm section for a chorus or two, then come out of it right on time. That was pretty far out there. One night, probably after the Frank Zappa concert at Celebrity Theater on May 26, 1975, Captain Beefheart (Don Van Vliet) sat alone in a back booth just behind Prince so he could see the keyboard, and listened for a couple of sets while we were there. Pete’s SF friend George Duke also visited and may have sat in one night.

I think I first played with Prince on one of those big band talent nights at the Skyroom, subbing on second alto. I remember the great singer Francine Reed sat in on Prince’s arrangement of “My Funny Valentine.” It’s normally an alto feature, and the intro is an almost atonal variation on “If You Could See Me Now,” with nothing to help the singer get the key or starting note. Francine just stood there looking at Prince after the intro during a long fermata on an ambiguous, dissonant chord. (There’s a link to audio and PDF of the arrangement above.) She said “Prince, you’re so heavy.” The place cracked up. He apologized, led her in, and she sang it beautifully, of course.

Along with often hearing him play, I’d also often see Prince Shell in record stores. He collected records and listened to music voraciously, going to thrift stores like the Salvation Army and Goodwill as well as Tower Records and the used record stores. When I got to know him and visited his house, by myself or with Lewis Nash, we often got into a listening session that might last for hours, and could include literally everything from rural blues to Roger Williams to Stockhausen to Sonny Rollins. He made compilation cassettes of his favorite tracks and gave them to us, and later mailed them to me in Boston and New York, with detailed handwritten track listings. The compilations had names like “Gems.” I’d also see him in the audience at clubs and concerts pretty often. When Sonny Stitt came to town as a single and played with a local rhythm section including Charles Lewis on piano, Prince was there. And visiting musicians like Malachi Favors, Pat Patrick, and others, especially people he came up with in Chicago, would look him up and hang out with him when they were in town. When Pat Patrick was in Tempe with the touring version of the show “Bubblin’ Brown Sugar,” Prince brought him and guitarist Mark Elf to a Sunday afternoon jam session Ted Goddard and I hosted at The Old Mill in Tempe (with Hamilton Sterling-bass, and Keith Miles-drums), and Pat sat in with us on flute. It was not easy for me to get Prince to talk about himself and his experiences, but he liked to talk about great music he had heard, and would sometimes tell funny stories about musicians, like the time he ran into Ahmad Jamal and didn’t realize, or forgot, he had changed his name, and said “Hey, Fritz, what’s happening?” Ahmad was not amused, apparently. He also told me “Sun Ra says he’s from Saturn, but it’s not true — I met his mother.” (The fact that he knew all these people personally helped lead me years later to writing a master’s thesis about Sun Ra, with oral history interviews.) Prince told me that Muhal Richard Abrams was a fantastic jazz arranger before he began writing avant-garde music, but that very few people knew about the great music he made before the Experimental Band in the 1960s. He turned us on to many relatively obscure players, little-known sides of known players, and rare and exceptional tracks.

Lewis Nash and I produced “An Evening of Creative Improvised Music” at the ASU Music Theater on January 21, 1980. The concert was well attended and reviewed in the Arizona Republic, and mentioned in Downbeat magazine. Along with the Nash-Chase Duo and ensembles with Mike Lake and Doug Robinson on trombones and Keith Miles on percussion, the concert featured a 33-minute solo piano performance (audio above) by Prince Shell that was unlike anything we ever heard him do, before or after. It was, at the same time, a medley of blues, standards, jazz tunes, and classical pieces, and a kind of postmodern stream-of-consciousness performance where any thought or memory might be explored without inhibition, from “Chopsticks” to repeating a Debussy phrase over and over with one note changing.

I got to play with Prince in Skyroom manager Mary Bishop’s (now Mary Perret) Roots of Jazz concert series, the BIg Band and Bird ‘n’ Bebop (2.18.80) concerts. These were big, well-attended events. We played the big band music at the Skyroom and the Boojum Tree. Also in 1980, the last few months before I moved to Boston, I led a steady gig at the Skyroom with vocalist Helen “Lady J” Jones. When possible, I hired Prince to play piano. The problem was, he didn’t usually have phone service or a car. So you’d have to go to his house and knock on the door. Prince lived in a small adobe house with evaporative colling (no air conditioning) where his mother had lived before, at 2702 E. Atlanta. (It’s since been torn down.) There were times when was home but didn’t answer — too busy writing, and/or also possibly concerned because he had been robbed there. If he answered, you might hang out and listen to music for a while, and if he accepted the gig, you might have to make arrangements to pick him up, or he might get a friend to drive him. John DIxon (radio DJ, A&R man for record labels, and Arizona’s music historian) and a friend helped Prince get a car at one point, but it didn’t last long. So hiring him was a challenge, but well worth it when possible, because he was one of the greatest musicians around, always fresh, creative, and inspiring, and very knowledgable.

Around the time I moved to Boston in 1980, Lewis Nash was forming his band Pendulum, and it included John “School” (formerly Schoolboy) Porter-tenor sax, Prince Shell-piano, and Tom Golden-bass. This was another top Phoenix jazz group that lasted until Lewis moved to New York to join Betty Carter.

In July 1982, I was back from Boston to see family, and I organized a concert at the ASU Music Recital Hall with my visiting friend Steve Adams-soprano sax and flute, me-alto and tenor saxes, Prince Shell-piano, Warren Jones-bass, and Ted Connell-drums. We rehearsed and did a mixture of jazz standards and originals. Prince did a stunning arrangement of “I Got it Bad” with trio. The transcription and recording are above. I’ve used Bob Elkjer’s transcription of this for decades as an example of jazz piano voicings and reharmonization. It’s a masterpiece. I adapted it for Your Neighborhood Saxophone Quartet and we recorded it on our CD Wolftone (Coppens, 1993).

After leaving Phoenix, we’d always try to look Prince up when visiting, find out where he was playing (solo piano at the Pointe South Mountain for a while, for example) and hear him, or meet for lunch — he liked cafeterias — or hang out at his home and listen to records. This happened a few times through the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Prince started to send me photocopies of his big band arrangements (and some for smaller groups, 4-6 horns) — there’s a list of the 45 arrangements I have below. His writing is phenomenal: it combines a deep knowledge of bebop and swing language and effective orchestration with unique uses of dissonance and reharmonization, and some surprising formal elements like juxtapositions, minimalist ideas, and transitions. He never (to my knowledge) put his name on a chart, and he would freely blend things copied from records with original ideas. He was writing functional music for bands to play, often starting by doing a record copy, and exploring his creative ideas in the process, but he didn’t seem to be concerned about getting (or giving) credit for elements of the arrangements. He often couldn’t remember where things had come from, when I asked. But most of his arrangements had significant highly original passages.

I put on a faculty concert of his big band music at the Berklee Performance Center (2.6.85), with Dominique Eade-voice, Gordon Brisker-tenor sax plus the members of Your Neighborhood Saxophone Quartet, Tim Hagans and Bill Mobley-trumpets, Donald Brown-piano, etc. I organized two recording sessions to record many of the arrangements with Boston players (8.12.86, 7.19.89). We also did a “Prince Shell & Friends” recording session at Cereus (7.21.91) with Prince and Helen “Lady J” Jones-voice, me-alto, Brian Sjoerdinga-tenor, Ted Goddard-guitar, John Daley-bass, and Tom Goodwin-drums in various combinations. In the 1990s, I performed several of his arrangements with student groups I conducted: the Tufts University Big Band (with Ingrid Jensen as a guest on “Moontrane” and others) and the NEC Jazz Orchestra. I hired Prince to write six 4- to 6-horn charts around 1994, and recorded those in New York (8.31.95) with musicians including Ingrid Jensen and Ron Horton-trumpets, Dave Panichi-trombone, Jay Brandford-bari, David Morgenroth-piano, and others. (None of these recordings were really intended for release, and I have most of them only on cassette tapes which I’m gradually digitizing.)

Prince moved back to his hometown of Lott, Texas in 1992 to take care of an aunt, and announced that he was leaving music. There were a couple of big going-away parties including one I attended at Malee’s Thai restaurant in Old Town Scottsdale. Prince wrote some letters from Lott, saying he was writing a bit but not playing. But after his aunt passed away not many years later, Prince came back to Phoenix and was back to playing, writing, and listening. Guitarist Ted Goddard formed a 10-piece band and recorded Prince’s music, with Prince on piano, and organized gigs. There were rehearsals at the Musicians’ Union hall, tributes, events when Lewis Nash was back in town, and local recordings with Ted’s groups, and singer Gaynel Hodge. A 2001 tribute at Mesa Community College, with Lewis Nash, Charles Lewis, and MCC jazz director Grant Wolf present, was an especially moving event for Prince and everyone there. In the mid-2000s, Prince became ill with prostate cancer and moved in with drummer Tom Goodwin, a close friend and supporter for many years, then lived in Veterans housing, and eventually a downtown Scottsdale nursing home where he spent his last months in late 2006 and early 2007. Prince passed away there on April 11, 2007.

Prince Shell is still remembered as a huge creative force, positive role model, and key member of the Phoenix music community.

He’s also remembered by Chicago musicians, some of whom knew nothing of his time in Phoenix. In early 2014, I performed and recorded with the Frank Walton-Yoron Israel Sextet at University of Chicago. In one of the rehearsals, Frank pulled out an arrangement of Richie Powell’s “Time” that was obviously in Prince Shell’s hand, and I asked about it. It turned out Frank knew Prince not only from Chicago, but from Tennessee State University in Nashville. He considered Prince an important mentor, too. I heard similar things from Dr. Warrick Carter, former dean of faculty at Berklee and president of Columbia College-Chicago — memories of Prince’s amazing arranging ability and playing, and his influence. He told me that he saw Prince writing out an arrangement on top of the piano, while playing a gig. (Prince never wrote scores, except after the fact when I asked him for one — he was one of those old-school arrangers who could hold an entire original arrangement in his head and write it directly on the transposed parts, which is almost inconceivable to most musicians today.)

There are many people who knew Prince Shell longer and better than I did and I hope they will record their thoughts about him. Lewis Nash, Tom Goodwin, Mary (Bishop) Perret, Charles Lewis, David Valdivia, John Dixon, and the late Emerson “Sleepy” Carrethers, Helen “Lady J” Jones, John “School” Porter, and Dave Cook, and probably many people I am forgetting or didn’t know, were all friends, as were his DuSable classmates and Chicago, Tennessee State, Navy, Air Force, and other bandmates.

When I listen to his playing and writing, I’m reminded how much his music is part of me and the way I play, write, listen, and think as a musician. There are probably hundreds of people who feel the same way.

Prince’s friends Charles Lewis and Patricia Myers told Sonny Rollins, after a local concert, that Prince was not well and in a nursing home in Scottsdale AZ. Sonny came to visit him the next day before leaving town. Sonny Rollins was one of Prince’s favorite musicians, along with Bud Powell, Charlie Parker, and a few others. Prince had arranged a “symphonic fantasia” of Rollins’ themes. Shortly after this, I had the opportunity to visit Prince there and show him the Boston Globe headline showing Deval Patrick was elected Governor of Massachusetts (in Nov. 2006). Prince had stayed with his friend Pat Patrick and family, including Deval Patrick as a baby, in their south side Chicago apartment in the mid-1950s. He had no idea that Deval Patrick had gone into politics until seeing the paper. Deval Patrick was the second African-American governor in the U.S. since Reconstruction. Photo: Charles Lewis, November 28, 2006.

45 Prince Shell arrangements in my collection. I’m hoping to convert more to computer notation so they are easier to share, copy, and read, although his hand notation is very legible. If you’re interested in playing or studying Prince Shell’s arrangements, please write me via the Contact page or at aschase-at-berklee-dot-edu.

Ted Goddard, Tom Goodwin, and others have overlapping collections of his work.

*About Captain Walter Dyett and DuSable High School’s music program and alumni:

Excerpt from my MA Ethnomusicology thesis, Sun Ra, Sun Ra: Musical Change and Musical Meaning in the Life and Work of a Jazz Composer by Allan S. Chase (Tufts University, 1992):

Early Band Members; DuSable High School

It was around 1948 that Sun Ra began to meet the young Chicago musicians who would become core members of his bands for the rest of his career. Many of them were students at DuSable High School, located at the corner of 49th Street and Wabash.[1] The high school was renowned for its excellent music program. "Captain" Walter Henry Dyett (b. 1901, d. 1969),[2] the band director there, was regarded as something of a living legend by Chicago musicians. A violinist, banjoist, and guitarist, he had played with Erskine Tate's orchestra at Chicago's Vendome Theater (probably in the 1920s) and had conducted an army band. His long years of dedicated teaching at the school (1931-ca. 1955?), colorful language, demanding style, and constant emphasis on discipline and humility all contributed to the aura around him. A former student, bassist Richard Davis, said, "Maybe you weren't afraid of the cops, but you were afraid of Captain Dyett" (Clarke 1989:366).

Dyett's charisma was also enhanced by the accomplishments of his former students. The list of Dyett's DuSable High School music program alumni is virtually a "Who's Who" of Chicago jazz. Among Dyett's students were:

Nat "King" Cole (b. 1917)-piano, voice

Von Freeman (b. 1922)-tenor saxophone

Bruz Freeman (birthdate unknown)-drums

George Freeman (birthdate unknown)-guitar

Bennie Green (b. 1923)-trombone

Dorothy Donegan (b. 1924)-piano

Dinah Washington (b. 1924)-voice

Martha Davis (birthdate unknown)-piano, voice

Gene Ammons (b. 1925)-tenor saxophone

*Victor Sproles (b. 1927)-bass

Bo Diddley (Ellas McDaniel) (b. 1928)-violin, guitar

E. "Prince" Shell (b. 1928)-valve trombone, piano, arranger

Johnny Griffin (b. 1928)-tenor saxophone

*Laurdine "Pat" Patrick (b. 1929)-saxophones, flute

Richard Davis (b. 1929)-bass

John Jenkins (b. 1931)-alto saxophone

Clifford Jordan (b. 1931)-tenor saxophone

*John Gilmore (b. 1931)-tenor saxophone, clarinet

*Robert Barry (b. 1932)-drums

Leroy Jenkins (b. 1932)-violin (flute and alto sax in high school)

Donald Rafael Garrett (b. 1932)-bass (clarinet or saxophone in high school?)

*Richard Evans (b. 1933)-bass, arranger

*Charles Davis (b. 1933)-baritone saxophone

*Julian Priester (b. 1935)-trombone, arranger

*Ronnie Boykins (b. 1935)-bass

Eddie Harris (b. 1936)-tenor saxophone

Andrew Hill (b. 1937)-piano (mellophone in high school)

Joseph Jarman (b. 1937)-saxophones

Wilbur Campbell (birthdate unknown)-drums[3]

Jerome Cooper (b. 1946)-drums[4]

Fred Hopkins (b. 1947)-bass[5]

(* Musicians who later recorded with Sun Ra.)

Captain Dyett's dedication to his music program set an example for the students. He organized an annual series of extra-curricular shows, the Hi Jinks, to raise money for the music program. Part of the proceeds was used to buy instruments for the students, since the school system did not provide them. The shows also gave many young musicians their first paying job in music. Dorothy Donegan recalled that the student members of the "Booster band" were paid one dollar per night for the four nights of Hi Jinks performances when she was a student (Travis 1983:300).

Joseph Jarman, a charter member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians and long-time member of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, was one of Dyett's last students at DuSable. Bob Rusch asked him, "What was the magic for you there?"

"Capt. Walter Dyett--that was the magic. He was just an extraordinary man, also an extraordinary musician and extraordinary teacher. He had this capacity to put into all these very young students from this kind of rough city life background. . . the idea of self-realization, of self-esteem . . . . And he was able to give his students very strong ideas of what the purpose of being is about. And he was always extremely positive even in his most disciplinary moments. I mean he would beat you on the fingers with your drum stick if you didn't do your drum lesson but in doing that you would understand that the reason you are doing the drum lesson is so you can learn the arts of concentration, so you can learn projection. And music was his vehicle to instill these qualities into his students--I think that was the most important magic that he had going.” (Rusch 1979c:3)

As Sun Ra began to select musicians for his own band, Dyett's students seemed to be ideal candidates. The ensemble skills, discipline and dedication they had learned at DuSable prepared them well for Sun Ra's eventual demands.

[1]Until 1936, the school was called Wendell Phillips High School (Clarke 1989:365, Travis 1983).

[2]See Clarke (1989:365-6).

[3]Washington, Campbell, Diddley, George Freeman, Bruz Freeman according to Clarke (1989). Clarke also lists comedian Redd Foxx (John Sanford, b. 12/9/22) and AACM bassist Fred Hopkins (b. 10/11/47) as former students of Dyett's, but Hopkins probably attended DuSable after Dyett retired. The others are listed in multiple sources, including Travis (1983), Spivey (1984), Clarke (1989), Wilmer (1977), Kernfeld (1989), Feather (1960, 1976), and/or were listed by Barry, Shell, or Evans in interviews or conversations.

[4] According to Henry Threadgill, Easily Slip Into Another World: A Life in Music (NY: Knopf, 2023), p. 262. Thanks to Bob Blumenthal for this reference.

[5] Fred Hopkins was a student of Walter Dyett’s according to John Litweiler’s LP notes for Air’s Air Time album (Nessa, 1978), and Threadgill (ibid, p. 213). Thanks to Bob Blumenthal for this reference.

NOTE: Sun Ra discographer Robert Campbell has done a lot of research on Chicago jazz of the 1940s and ‘50s, some of which appears on his “Red Saunders Research Foundation” web page here: http://campber.people.clemson.edu/rsrf.html